How, When & Where Was HWA Introduced? The Gilded Age Garden Hypothesis

Little attention has been given to the historical introduction of the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid to the Eastern US. HWA was first identified from a 1951 hemlock sample, collected in Richmond VA. But important questions remain about this introduction: Where did this HWA come from? Was Richmond the only HWA introduction site in Eastern North America? What was the mechanism for introducing HWA? And did this introduction really occur as late as 1951?

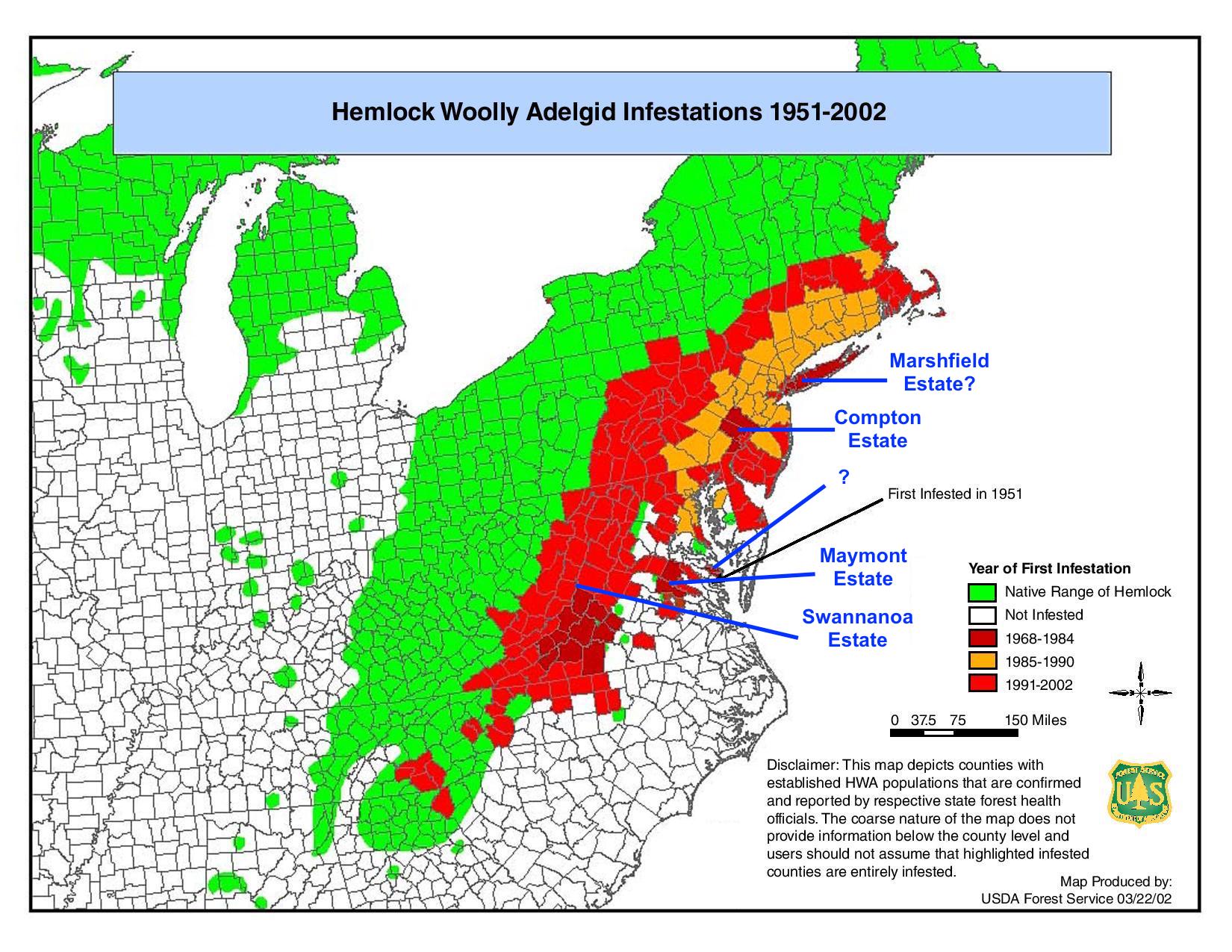

Further historical research provides an update on the introduction(s) of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid to the eastern US. This research indicates multiple HWA introductions originated in southern Japan during the 1910-1915 era, about 40 years before the discovery of HWA in Richmond. And in addition to Richmond, several other sites were involved, as indicated in the four “Gilded Age Garden” sites, which are labeled in blue on the map below. Recent scientific research on the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid provides data that are critical to addressing these historical issues. One area of research has used statistical analysis of DNA to identify all known HWA lineages and their world distributions. And this analysis has definitively identified the origin of HWA introduced to the eastern US as Southern Japan!

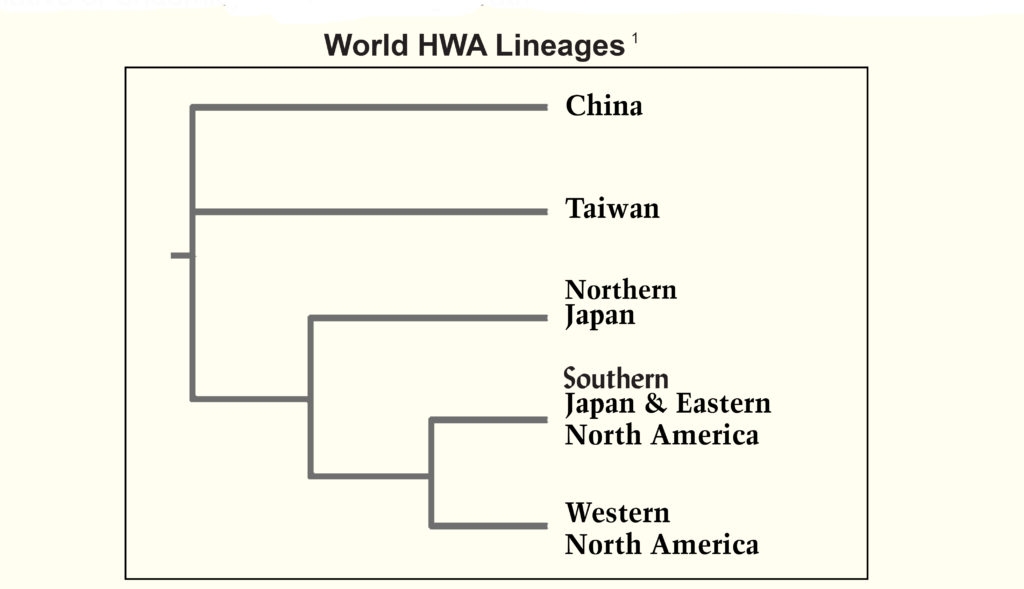

Recent scientific research on the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid provides data that are critical to addressing these historical issues. One area of research has used statistical analysis of DNA to identify all known HWA lineages and their world distributions. And this analysis has definitively identified the origin of HWA introduced to the eastern US as Southern Japan!

The HWA genomic research published by Nathan Havill and associates (in 2006 & 2016) has transformed our understanding of world Hemlock Woolly Adelgid genetic diversity! This research has not only documented the existence of multiple, genetically distinct, HWA lineages in countries around the world. It has also clearly identified our HWA “import” as that native to Southern Japan. Below is a chart presenting the five biologically distinct HWA lineages identified in Havil’s 2006 DNA analysis.

(It is interesting to note that the first USDA-approved predator for HWA, Sasajiscymnus tsugae, was collected in 1992 in southern Japan, the origin of our introduced HWA. But this was over a decade before Havill’s DNA research confirmed Southern Japan as the origin of the HWA present in the eastern US. This HWA predator discovery was based on field observations (by Mark McClure, CAES) of healthy American hemlocks (Tsuga canadensis) and Japanese hemlocks (Tsuga seiboldii) co-existing with HWA in Osaka area garden settings. So, Havill’s later research on HWA origins confirmed Sasajiscymnus tsugae as a native predator for our HWA “import” after it had already been approved for US release.)

How and When Was Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Introduced?

This question was first raised in 2008 by USDA researchers Nathan Havill and Michael Montgomery. They followed up Havill’s earlier DNA research discovery for HWA origin in Southern Japan by searching for a “Japanese connection” in historical documents for Maymont Estate in Richmond, Virginia – which was the site of the original HWA discovery. And this search led to archival reports on a 1911 Japanese Garden construction project at Maymont, involving international Japanese Garden designer, Y Muto.

Biological research on HWA indicates that the transfer of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid from Japan would require live “host plants” from one of two species of conifers (native to southern Japan) on which HWA can survive. These two conifer species are the Southern Japanese Hemlock (Tsuga seiboldii), which hosts the HWA asexual reproductive cycle, and the Tigertail Spruce (Picea torano / Picea polita) which hosts the HWA sexual reproductive cycle. And Muto’s affiliation with the world-famous Yokohama Nursery provided his US garden clients with a commercial source for both of these Japan-origin landscape plants.

In 2017 Patrick Horan extended the search for additional Muto-affiliated ‘Gilded Age Garden’ sites to encompass the entire eastern US. This extended search has located documentary evidence for three more early 20th century Japanese Gardens involving Mr. Muto – in addition to that at Maymont Estate in Richmond. These additional “Muto garden sites” include Swannanoa Estate in the Virginia mountains, which was created by James and Sallie Dooley of Maymont, as well as John and Lydia Morris’s Compton Estate in Philadelphia. Finally, an unidentified Muto Japanese Garden site on Long Island is represented here by “Marshfield Estate”. Note that these locations also correspond to the early HWA introduction sites identified in the USFS maps below. So this research provides a Muto-affiliated ‘Gilded Age Japanese Garden’ site corresponding to each of the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid introduction sites indicated by the USFS monitoring data below!

While the evidence for Muto-affiliated garden sites in Long Island, Philadelphia, Richmond and the central Virginia mountains may be persuasive, it doesn’t prove that HWA was introduced at these sites. However, it does provide a plausible hypothesis that is consistent with both USFS monitoring data for HWA discoveries and with existing archival documentary evidence for these early 20th Gilded Age Garden sites. This documentary evidence includes 1) Muto’s participation in the construction of early 20th century Japanese Gardens at all four sites, 2) the presence of Muto-era Japanese Hemlock and Spruce trees located at these garden sites and 3) invoice documentation for purchases of such Japan-origin landscape plants from the Yokohama Nursery in Japan.

Gilded Age Japanese Garden Sites, 1910-1915

The map above presents the four Muto-affiliated Gilded Age Japanese Garden sites that have been identified to date. The gardens at two of these sites, Maymont and Morris Arboretum (Compton), are open to the public and have Muto-era (1910-1915) Tigertail Spruce (Picea torano / Picea polita) present. The two Tigertail Spruce at Morris Arboretum have documented Yokohama Nursery origin, but all records for the garden at Maymont (and its single Tigertail Spruce) were classified as Sallie Dooley’s personal papers and were destroyed, per her will. And this destruction also included records for the Dooley gardens at Swannanoa.

Three of these sites involve wealthy, internationally-known garden owners: John and Lydia Morris of Compton Estate in Philadelphia, and James and Sallie Dooley at both their Maymont Winter Residence in Richmond and their Swannanoa Summer Residence in the central Virginia mountains. Both John Morris and Sallie Dooley were noted for their active participation in international horticulture in the early 20th century. Morris had employed Mr Muto for multiple turn-of-the-century Philadelphia area Japanese garden projects, including several on his own Compton estate. And James Dooley described his wife Sallie’s garden orientation as involving the “purchase [of] the most costly evergreens from all parts of the world” – a budgetary topic on which he was apparently well-informed! Plus, century old Southern Japanese Hemlocks and Tigertail Spruce are present at Maymont and Compton (now Morris Arboretum) gardens.

But for Long Island, beyond a report (in the Maymont archives) of Muto’s 1910 involvement in a Japanese garden project in Long Island, there is no documentary evidence indicating the specific name or location of this garden. As a large Japanese Garden project pictured below in 1015, the Marshfield Estate in Cedarhurst NY, owned by Mr. & Mrs. George W. Wickersham, fits the profile and time frame, but there is no evidence linking Mr Muto to this particular LI garden site.

Japanese Garden at Marshfield Estate, circa 1915

This garden is reportedly no longer in existence. And without further evidence connecting this site to Muto or Japan-origin plants, this should be considered only as a “possible” Long Island garden candidate … pending further historical research on Long Island gardens of that era. There were multiple Gilded Age Garden sites on Long Island in the early 20th century. And during this era, the Yokohama Nursery had its eastern US sales branch in Brooklyn, NY. So the Japanese origin landscape plants of interest here would have been available to other knowledgeable (and affluent) Long Island gardeners.

This garden is reportedly no longer in existence. And without further evidence connecting this site to Muto or Japan-origin plants, this should be considered only as a “possible” Long Island garden candidate … pending further historical research on Long Island gardens of that era. There were multiple Gilded Age Garden sites on Long Island in the early 20th century. And during this era, the Yokohama Nursery had its eastern US sales branch in Brooklyn, NY. So the Japanese origin landscape plants of interest here would have been available to other knowledgeable (and affluent) Long Island gardeners.

Where Was Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Introduced?

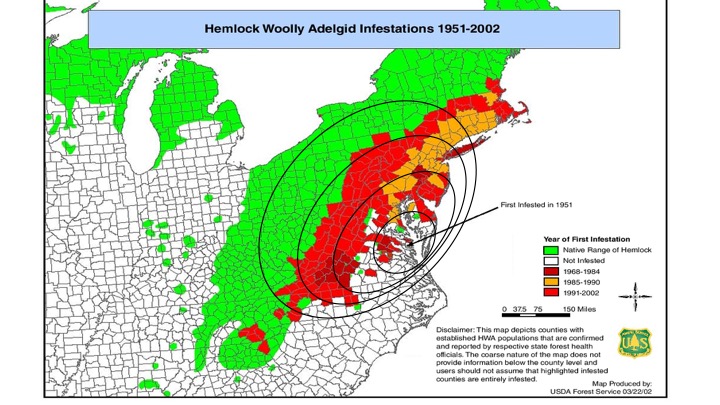

Havill’s DNA analysis confirms that the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid introduced to the eastern US came from Southern Japan, but where did this introduction occur – at a single site in Richmond, VA … or at multiple locations in the Eastern US as suggested above? We can use USDA historical data on HWA observations during the 30+ year period from 1968-2002 to address this question. But please note that these USDA-collected data do not represent dates for the “First Infestation” of HWA (as labeled). Instead they are dates for the “First Observation” of HWA by USDA representatives, which began in the mid-20th century – about 50 years after the actual HWA introductions. (Obviously, USDA observations could not begin before the presence of HWA in the eastern US was recognized – sometime in the mid 1960’s.)

The historical map prepared by the US Forest Service uses county-level data representing the first year in which HWA was confirmed present in each county in the Eastern US. Note that the sites of earliest HWA observations (1968-1984) are marked with the darkest red color, the next set of HWA observations (1985-1990) are marked a tan color. And later HWA observation sites (1991-2002) are marked bright red. So this coloring provides a temporal dimension to HWA discoveries.

To interpret these data, we can ask: Where are the early Hemlock Woolly Adelgid introduction sites in the Eastern North America? And what is the pattern of HWA movement over time? For the introduction site question, we can note 5 geographically distinct sites where early HWA infestations were reported, as indicated by the dark red coloring. These sites were 1) Central Virginia mountains, 2) Richmond, 3) coastal Virginia, 4) Philadelphia and 5) Long Island. For the pattern of movement question, we can note the transition on the map from dark red areas to tan areas to bright red areas, where the HWA are observed moving out to counties with previously uninfested hemlock areas.

My objective here is to use these historical USFS data on HWA distribution and dispersion to test an “HWA introduction hypothesis” about single vs multiple HWA introduction sites. And again, a cautionary reminder that these USFS data do not represent dates for the “First Infestation” of HWA (as labeled), instead they represent dates for the “First Observation” of HWA by USDA personnel. And the evidence presented above shows that the actual historical introduction dates (1910-15) for the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid from Southern Japan are much earlier than those indicated on the USFS map.

The first map below depicts the hypothesis of a single-HWA-introduction-in-Richmond, which has dominated most USDA accounts. The ovals represent hypothesized spread, over time, from a specified point, in this case Richmond, VA. Here, this hypothesis of outward distribution from a single site in Richmond works reasonably well in accounting for Hemlock Woolly Adelgid outflow in the Southeast. But it does not account well for the observed HWA distributions in the northeastern US, which are much more extensive than would be expected under the single Richmond site hypothesis.

Single Site Introduction Hypothesis for Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

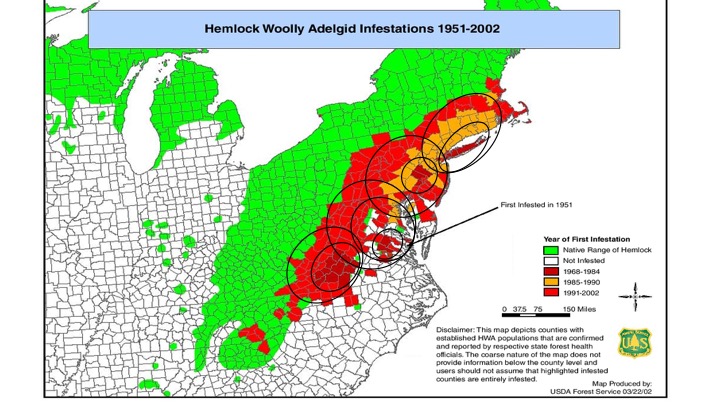

To interpret these data, we can ask: Where are the early Hemlock Woolly Adelgid introduction sites in the Eastern North America? And what is the pattern of HWA movement over time? For the introduction site question, we can note 5 geographically distinct sites where early HWA infestations were reported, as indicated by the dark red coloring. These sites were 1) Central Virginia mountains, 2) Richmond, 3) coastal Virginia, 4) Philadelphia and 5) Long Island. For the pattern of movement question, we can note the transition on the map from dark red areas to tan areas to bright red areas, where the HWA are observed moving out to counties with previously uninfested hemlock areas.

The second map (below) presents the competing multiple-HWA-introduction-sites hypothesis, using four early Hemlock Woolly Adelgid introduction sites suggested by the USFS data. These early HWA observation sites (marked in dark red on the USFS map) are located in the Central Virginia mountains, Richmond VA, Philadelphia PA and Long Island NY, which correspond to the gilded age garden sites documented above.

Multiple Site Introduction Hypothesis for Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

This multi-site hypothesis seems to work much better in accounting for Hemlock Woolly Adelgid dispersion throughout the eastern US – for northern as well as southern areas. So these historical data provide additional support for the Gilded Age Garden hypothesis presented above. (Note that the coastal Virginia site, indicated on the Gilded Age Garden map with a ?, is well outside the native hemlock range and climate. So this is more likely a garden HWA transfer from the Dooleys’ Richmond/Maymont estate, rather than an introduction from Japan.

What Would You Like to Learn More About?

Biological Control of HWA, with Sasajiscymnus tsugae

Planning and Implementing Predator Beetle Releases

Commercial Source for HWA predator beetles

Choice among HWA predator beetles

A Science-based Strategy to Protect Hemlock Ecosystems

Directions for Further Research

There are important differences between scientific applications to contemporary topics, as opposed to historical topics. For example, it is often possible to collect additional data to address different hypotheses that arise for contemporary topics, whereas historical inquiries depend on archival data. And it is rarely possible to go back in time to collect additional data to address historical topics (for example to check for the presence of HWA on imported plant specimens from Japan, circa 1910-1915). But here are some suggestions about possible additional archival data that would be relevant to this historical inquiry.

Further archival research will be needed to evaluate and elaborate the multi-site HWA introduction hypothesis proposed above. I welcome the participation of others in this research effort. And I acknowledge the helpful contributions of Curators Dale Wheary at Maymont and both Leslie Crane-Smith and Anthony Aiello at the Morris Arboretum, to my own documentary research efforts.

Another valuable research extension would involve the original HWA observation reports collected by USDA, which were used to construct the USFS historical county-level map utilized here. (The county-level data for the 1968-2002 period are available from USFS, but not the individual site reports from which these county-level data were derived.) So there remain some important unknowns about these original observational report data. For example, who were the USDA representatives reporting on Hemlock Woolly Adelgid sightings and where are the resulting site reports located?

My current hypothesis is that these data were collected by USDA County Extension offices in each state. And that would mean that these historical data for local HWA identifications are probably stored in USDA Extension archives at the land-grant universities in the respective states. But I have not yet been able to confirm the existence/location of these individual site records with officials at USFS or USDA.

Patrick Horan