What is the Future for Hemlocks

in Eastern North America?

This? |

Or this? |

The imported Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HWA) has brought widespread destruction to native hemlocks in the eastern US. The loss of hemlocks would be an ecological disaster for our forest coves and waterways, as well as for our neighborhoods and parks. As a keystone species, on which many other species depend, hemlocks provide critical shelter and habitat for a whole range of animal species including birds, amphibians, fish and mammals. And there are no apparent successors, native or otherwise, that could fill the critical ecological niche of the Eastern hemlock. So the hemlock’s demise would threaten all hemlock-dependent ecosystems.

Good News for Hemlock Recovery!

The threat of hemlock loss is real, but it is not inevitable. There is a USDA-approved predator beetle that can control Hemlock Woolly Adelgid on our native hemlocks and support the long-term survival and recovery of our native hemlock ecosystems in the Eastern US. That predator beetle is Sasajiscymnus tsugae – which is the native predator for our HWA “import” from Southern Japan. And this predator is commercially available to US landowners from a rearing facility in PA.

This natural restoration and recovery process is already underway in both wild and residential hemlock areas, where these HWA predator beetles have been released. See hemlock restoration. But human action is required to introduce these predator beetles to control HWA in all hemlock areas at-risk. Hemlocks on some public lands have received help from USDA, but protecting and restoring hemlocks on private lands requires your help.

It is widely recognized that biological control of hemlock woolly adelgid with HWA predator beetles is the key to long-term restoration and recovery of hemlocks in the eastern US. However a successful biological control program requires a predator that will be active on both HWA reproductive cycles, not just one. And recent research documents that this criterion excludes the Laricobius predator species, which feed only on one HWA cycle.

Once established, the USDA/APHIS approved Sasajiscymnus tsugae predator beetles will reduce HWA numbers to a level that will restore normal hemlock growth and allow HWA-damaged hemlocks to recover. And restoring the hemlocks will help restore important hemlock eco-systems! That hemlock restoration process is currently underway in eastern US hemlock areas where the Sasajiscymnus tsugae predator beetles have been released:

Researchers at UT found one of the original predator beetle species — Sasajiscymnus tsugae at eight of the 10 release sites in the Smokies and Cherokee National Forest. Some had spread 1.2 miles from the initial release site. Where the beetles were found, the hemlocks were alive.

Here is what predator-beetle-assisted Hemlock Restoration looks like:

(Note old foliage damage on lower branches and new foliage growth on upper branches)

The Sasjiscymnus tsugae predator beetles approved for release in the eastern US are so highly specialized that they require adelgids to survive and reproduce. So there is not a threat of these beetles affecting other, non-adelgid insect species. And this predators’ introduction and release in the US was approved by USDA/APHIS even before genetic research (below) determined that origin for our Hemlock Woolly Adelgid “import” was Southern Japan, which is also the origin for the predator beetle – Sasajiscymnus tsugae (St). And this predator beetle, with millions released by USDA/USFS on public lands, is now available to protect hemlocks on private lands as well.

The Sasjiscymnus tsugae predator beetles approved for release in the eastern US are so highly specialized that they require adelgids to survive and reproduce. So there is not a threat of these beetles affecting other, non-adelgid insect species. And this predators’ introduction and release in the US was approved by USDA/APHIS even before genetic research (below) determined that origin for our Hemlock Woolly Adelgid “import” was Southern Japan, which is also the origin for the predator beetle – Sasajiscymnus tsugae (St). And this predator beetle, with millions released by USDA/USFS on public lands, is now available to protect hemlocks on private lands as well.

Sasajiscymnus tsugae Predator Beetles Feeding at GSMNP

Wherever these voracious little black ladybug predators go, their first objective is finding Hemlock Woolly Adelgid on which to feed and reproduce. So releasing them on HWA-infested hemlocks will provide maximum benefit – to you and your hemlocks! And the Sasajiscymnus tsugae beetle larvae are even more voracious than the adults, as they feed on HWA eggs, larvae and adults to extend the HWA control process. And there is an approved commercial source for this predator available to landowners.

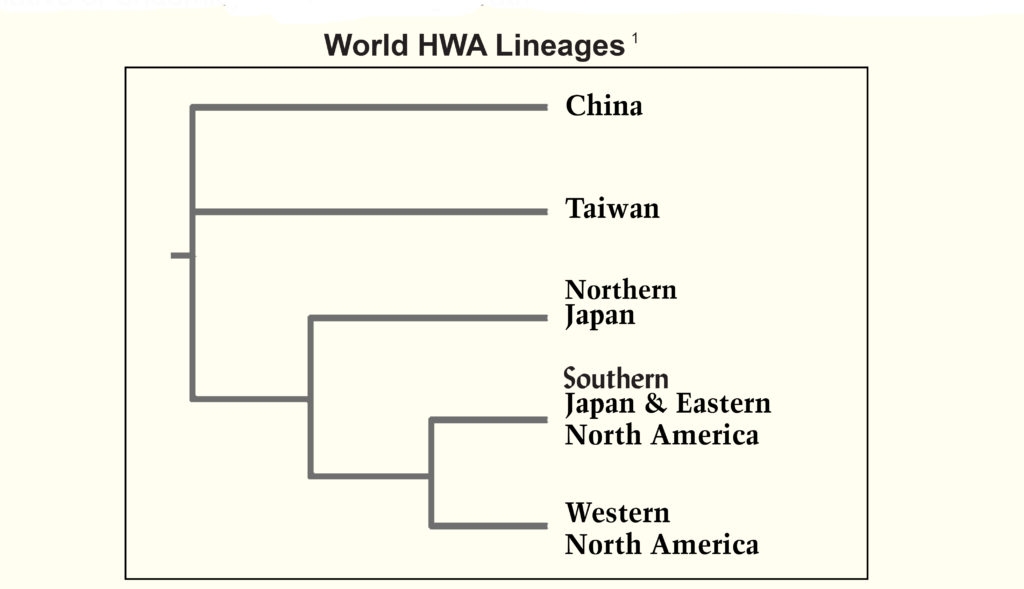

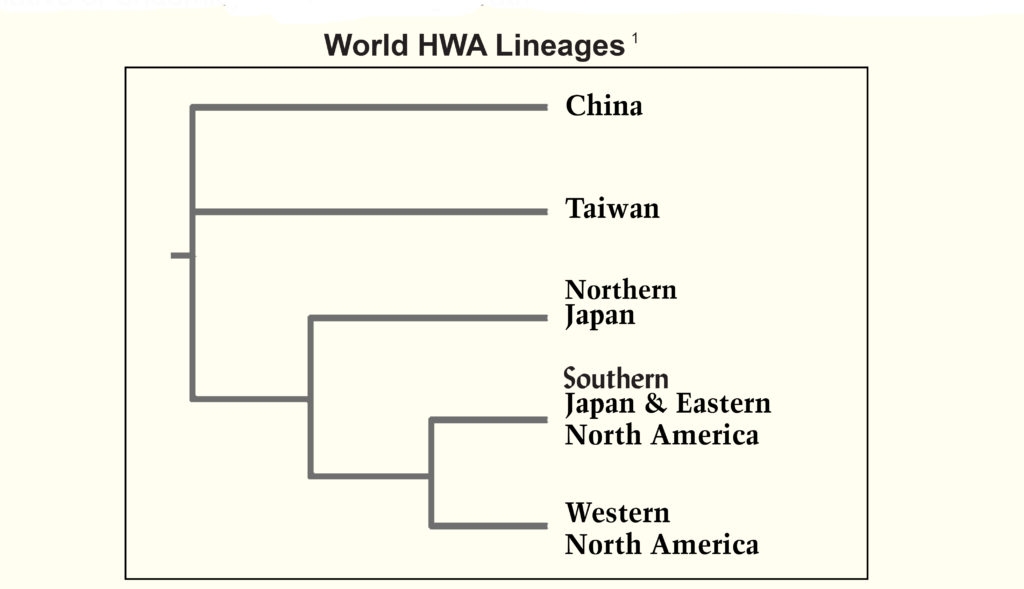

Where Did Our Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Come From ?

USDA-sponsored research by Nathan Havill and associates has transformed our understanding of the relationship between Hemlocks and Hemlock Woolly Adelgids around the world! Havill’s analysis (2006) of mitochondrial DNA collected from all known HWA populations identified the five genetically distinct HWA strains depicted below. But this analysis also determined that the HWA found in the eastern US are identical to the genetic strain found in southern Japan. And this confirms the source of our HWA pest introduction as southern Japan! But the good news is that the predator beetle (Sasajiscymnus tsugae) that controls HWA in southern Japan will also control that same HWA here in the eastern US! This predator is USDA-approved for US release and is readily lab-reared and available to private landowners during the Spring predator release season. Here is a link to the HWA predator-rearing Lab in PA, which offers predator beetles and HWA consulting to private landowners: Tree-Savers.

But the good news is that the predator beetle (Sasajiscymnus tsugae) that controls HWA in southern Japan will also control that same HWA here in the eastern US! This predator is USDA-approved for US release and is readily lab-reared and available to private landowners during the Spring predator release season. Here is a link to the HWA predator-rearing Lab in PA, which offers predator beetles and HWA consulting to private landowners: Tree-Savers.

How, When & Where was Hemlock Woolly Adelgid introduced to Eastern North America?

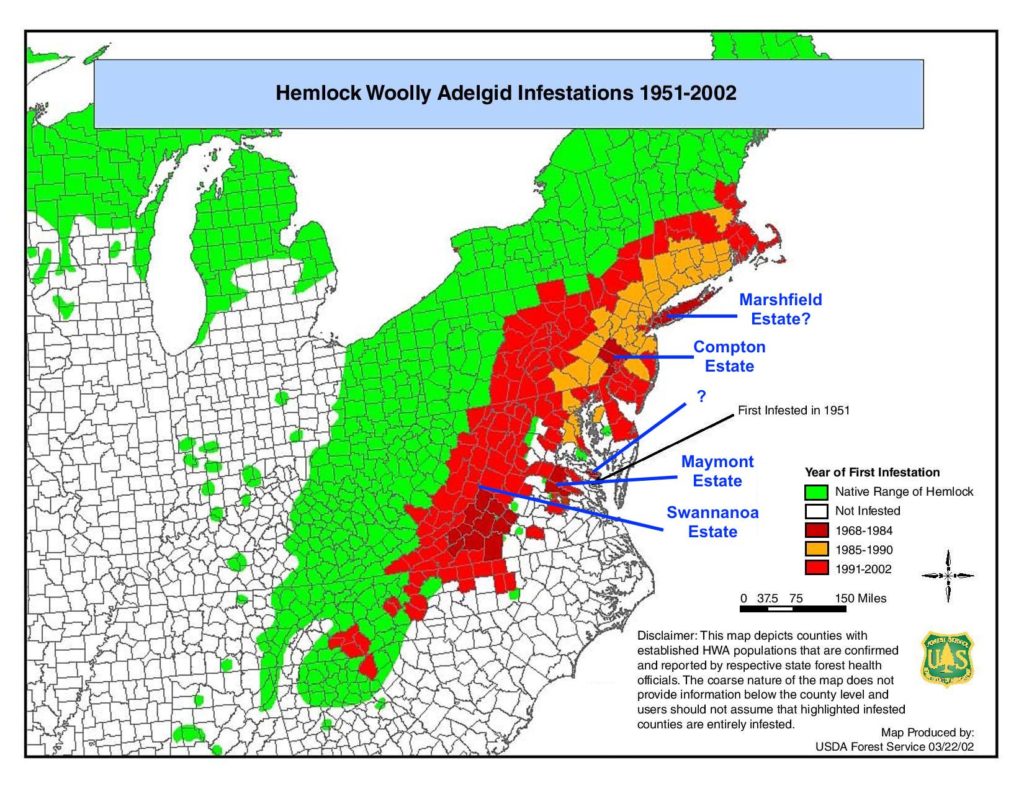

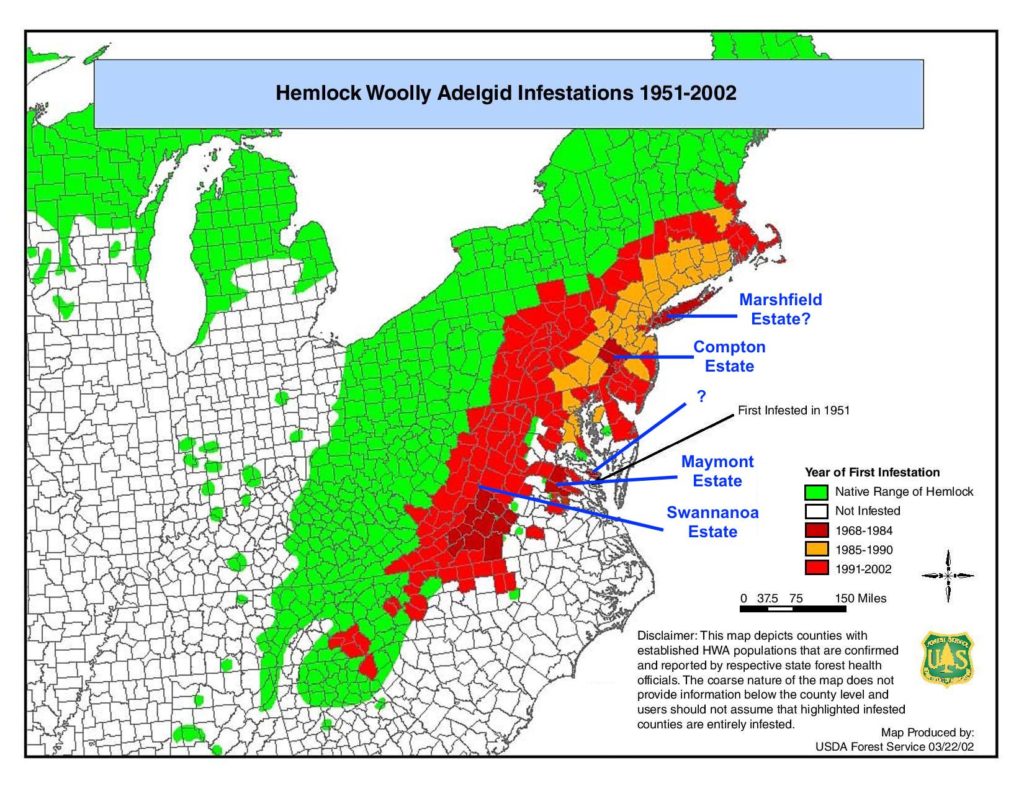

Havill’s DNA research on HWA origins, when combined with USDA monitoring data for HWA in the late 20th century, can provide a scientific foundation for researching the introduction of HWA into the Eastern US. This historical research strongly suggests that multiple US Gilded Age Garden sites contributed to HWA introductions from Southern Japan to Eastern North America. Plus, the timetable for these HWA introductions was not 1951, as commonly reported, but in the early 20th century (1910-1915) – about 40 years before its 1951 discovery in Richmond.

So the imported HWA population had been growing and spreading across hemlock ecosystems for over 50 years, before its presence was recognized by USDA. The map below shows some likely Gilded Age Garden sites that introduced HWA on imported conifers from Japan and the proximity of these garden sites to HWA infestation areas identified by USDA research (beginning in 1964). For more information on this research, go to Gilded Age Garden Hypothesis. (Note that the dates in the USDA historical map utilized below refer to the “Year(s) of USDA First Discovery” of HWA, not to the “Year of First Infestation” of HWA, as indicated on map.)

Proposed Gilded Age Garden Sites for 1910-15 HWA Introduction What would you like to learn more about?

What would you like to learn more about?

Purchasing Sasajiscymnus tsugae predator beetles, see Predator Beetle source.

Biological control of the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, see Biological Control.

How you and your community can participate in HWA biological control, see Community.

How genetic mutations can contribute to hemlock diversity, see Witch’s Brooms.