Choosing an HWA Predator Beetle: Laricobius nigrinus or Sasajiscymnus tsugae

The goal of the HWA biocontrol strategy is to achieve HWA population control which extends through both reproductive cycles of the hemlock woolly adelgid. HWA reproduction occurs in two consecutive cycles in Spring (sistens) & Summer (progrediens). And recent USDA research confirms that HWA biocontrol success requires predation on both of these HWA reproductive cycles.

All USDA-approved HWA predator beetles are “specialist” insects that feed exclusively on adelgids. And all are subject to a seasonal diapause in which they suspend activity in response to environmental conditions, such as temperature. So it is the timing of these diapause periods that is of critical importance for predator efficacy. In short, a summer-feeding predator will feed on HWA throughout both HWA reproductive cycles But a winter-feeding predator will only feed on the first HWA cycle, leaving the second (Summer) HWA reproductive cycle (which runs mid-May thru mid August) unaffected.

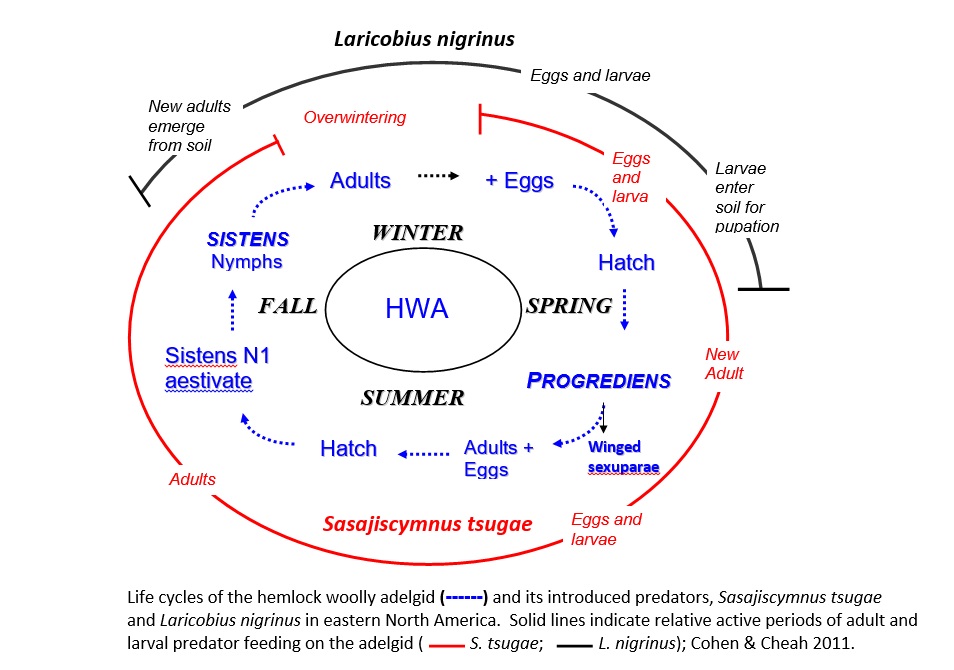

Below is a schematic diagram, prepared by Dr. Carole Cheah (CAES), that illustrates the predator/prey life cycles for Hemlock Woolly Adelgid and the two HWA predators currently available to private landowners in the eastern US. HWA (shown in blue) has two successive reproductive cycles (Sistens & Progrediens), extending from late Fall through the Summer, with a Fall diapause. The summer-feeding predator, Sasajiscymnus tsugae (shown in red) feeds and reproduces from early Spring through Fall, with a Winter diapause – providing predation on both HWA reproductive cycles. The winter-feeding predator, Laricobius nigrinus, shown in black, feeds and reproduces during the Winter and early Spring, with a Summer diapause. This provides predation on the first HWA reproductive cycle, but not on the second HWA reproductive cycle which continues through the Summer.

This shows that the life cycle of winter-feeding Hemlock Woolly Adelgid predators, such as L nigrinus, limits their predation to the first of the two consecutive HWA reproductive cycles (sistens, progrediens). However, recent USDA research has established that any first cycle HWA population control effects by winter-feeding predators will be “obliterated” by the second HWA reproductive cycle.

This shows that the life cycle of winter-feeding Hemlock Woolly Adelgid predators, such as L nigrinus, limits their predation to the first of the two consecutive HWA reproductive cycles (sistens, progrediens). However, recent USDA research has established that any first cycle HWA population control effects by winter-feeding predators will be “obliterated” by the second HWA reproductive cycle.

So winter-feeding predators, such as Laricobius nigrinus can only be successful as a supplement to a summer predator, such as Sasajiscymnus tsugae, which feeds on both HWA cycles*. This means that Laricobius predators cannot provide stand-alone population control for HWA in the eastern US! On the other hand, with its cycle of reproduction and predation across both HWA reproductive cycles, Sasajiscymnus tsugae can provide stand-alone HWA control.

* There has been some confusion concerning successful hemlock health recovery reports at the Grandfather Mountain Golf and Country Club (GGCC) in North Carolina. And these reports have sometimes overlooked the fact that this was a joint release site involving both Laricobius nigrinus and Sasajiscymnus tsugae. Here is documentation on this issue from Richard McDonald, who was responsible for the predator beetle releases at this GGCC site.

Summer-feeding HWA Predators

The life cycle of a Summer-feeding predator allows predation on both Spring and Summer HWA reproductive cycles to best reduce HWA population numbers. The first choice for a summer-feeding HWA predator beetle is Sasajiscymnus tsugae (St), which is the native ladybug predator that controls our HWA “import” in southern Japan.

St was the first HWA predator to receive USDA/APHIS approval and it has been widely released by US Forest Service on federal lands (National Parks and Forests) and some state lands in the eastern US. And this predator is also commercially available to private landowners, during the Spring predator release season, from a rearing laboratory in PA.

St was the first HWA predator to receive USDA/APHIS approval and it has been widely released by US Forest Service on federal lands (National Parks and Forests) and some state lands in the eastern US. And this predator is also commercially available to private landowners, during the Spring predator release season, from a rearing laboratory in PA.

Sasajiscymnus tsugae experiences a winter diapause in which it rests during the coldest part of the year (~ mid-November to mid-February in the southern Appalachian range). This winter diapause gives it considerable cold tolerance, and its summer feeding encompasses both HWA reproductive cycles (sistens & progrediens), which can extend through late July. Plus, this is the only HWA predator that produces multiple generations during its reproductive season and in which adult beetles survive to breed over multiple seasons.

Winter-Feeding HWA Predators

Laricobius rubidus is a native derodontid adelgid predator beetle that is widely distributed throughout the eastern US. It feeds primarily on the woolly pine bark adelgid (Pineus strobi), also a native insect that is found on the Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus). White Pine trees in the wild do not appear to be seriously affected by pine bark adelgid (PBA) infestations, but this can be a serious problem on stressed saplings. While L rubidus will feed on HWA, it prefers PBA for both feeding and reproduction. And so our native Laricobius rubidus has not proved an effective control agent for the imported hemlock woolly adelgid since the HWA introduction to the eastern US in the early 20th century.

Laricobius nigrinus is a predator beetle from the North American Pacific Northwest which is very closely related to our native L rubidus. Its preferred food in warmer coastal areas is the Pacific HWA, which is a different (genetically distinct) organism from the ( Japan-origin) HWA found in the eastern US. The Pacific HWA is not capable of attacking healthy western hemlocks (Tsuga heterophylla) in the wild, but typically is found on hemlocks that have been damaged or stressed (by natural or human actions).

Laricobius nigrinus is a predator beetle from the North American Pacific Northwest which is very closely related to our native L rubidus. Its preferred food in warmer coastal areas is the Pacific HWA, which is a different (genetically distinct) organism from the ( Japan-origin) HWA found in the eastern US. The Pacific HWA is not capable of attacking healthy western hemlocks (Tsuga heterophylla) in the wild, but typically is found on hemlocks that have been damaged or stressed (by natural or human actions).

Laricobius osakensis is a predator beetle that was discovered feeding on our HWA import in its native range in Southern Japan. In that area, it joins with Sasajiscymnus tsugae in protecting the southern Japanese hemlock (Tsuga seiboldii) from the same HWA that threatens our native hemlocks in the eastern US. This predator beetle has only recently received USDA approval for release in the eastern US, and is not yet available to private landowners.

Our Japanese HWA import has obviously not been controlled by our resident Laricobius rubidus. So the competition for the best winter-feeding addition to a predator cocktail with the summer-feeding Sasajiscymnus tsugae is between Laricobius nigrinus from the Pacific NW and Laricobius osakensis from Japan. Neither is native to the eastern US, but both are adelgid “specialist” predators which should not represent a threat to other native insects or plants. One glaring exception to this statement is the fact that the introduced L nigrinus is so closely related to the native L rubidus that the two species can hybridize, with unknown long-term implications for either species!

Leave a Reply